Parents – How to Talk to Kids about Suicide

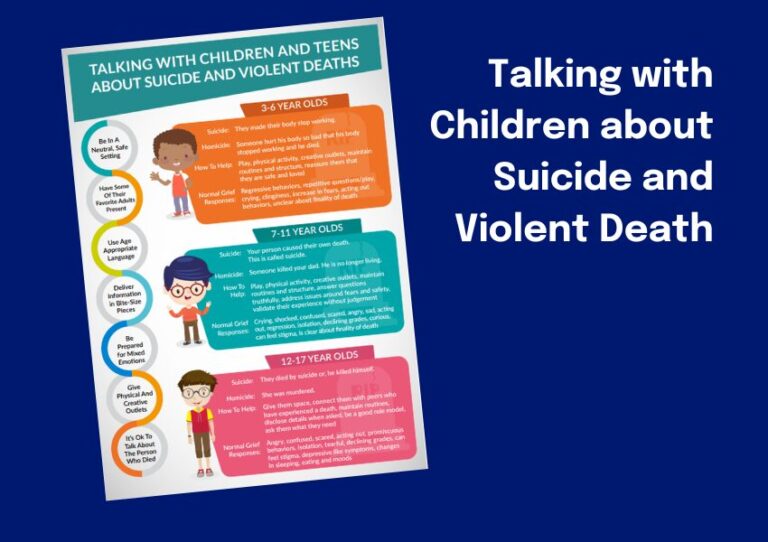

Adults often want to protect children from the harsh realities of life and find it difficult to talk about suicide with children. However, protecting them may take away opportunities to heal. As children hear adults talking about the death, they will create their own version of events. Age-appropriate, truthful information provides opportunities to address any concerns or misconceptions children have around the person’s death.

Many caregivers and parents also hesitate to discuss suicide out of embarrassment, confusion, or fear. Talking about depression, mental illness, and suicide takes away the stigma and opens up lines of communication that are essential as families support one another after a death. Below are suggestions and information to help you have these important conversations.

Many adults feel that children are too young to hear the truth about a death and are nervous to use the terms “died” or “suicide”. Using the phrase “died by suicide” will help you discuss the manner in which the person died. The term “committed suicide” can suggest a crime was committed and “completed suicide” can suggest an accomplishment was achieved.

Depending on the age of the children, the information they seek and need will vary. Provide basic facts and allow their questions to guide the conversation. Here are some examples to explain suicide and answer their questions:

“He died by suicide.”

“Dead means the body has stopped working, and it cannot be fixed.”

“Our thoughts and feelings come from our brain, and sometimes a person’s brain can get very sick – just like a body can. This is sometimes referred to as mental illness. This sickness can cause a person to feel really, really sad and hopeless. Some people feel like the only way their hurting and sadness will go away is to make their own body stop working.”

Encourage children to talk to adults their questions and feelings. “You probably have a lot of questions about what happened. You can always ask me and let’s brainstorm some other adults you can talk to.”

If they ask how it happened, provide truthful but simple information. “She took too many pills.” “He hurt himself and his body stopped working.”

To help your child through their grief, be present and actively listen without trying to make it better or by taking away their pain. Allow them to share what they are thinking and feeling and discuss the memories they have of the person who died. Share stories, use the person’s name, and show them that it’s okay to cry or laugh – help them see they are not alone on this journey.

Magical Thinking and Regrets

Some children believe they played a direct role in the death – a concept called magical thinking. They may think back on things they could have done or should or shouldn’t have said to the person who died. Regrets are a common part of grief, but sometimes these thoughts make them feel like they had a part in the person’s death. They feel their words or actions had enough power to influence someone to suicide. Remind campers that their person died because their brain was sick and not thinking clearly. Many factors play into why someone would choose suicide and no single factor caused the death.

How Children Grieve

Children grieving a death by suicide will experience a wide range of feelings and all of these feelings are normal. Children may express their feelings through behaviors rather than words. Help them find appropriate ways to express and release what is inside through art, activity, and play.

Younger children may also regress in their behaviors such as bed-wetting or needing an old comfort item. Usually these behaviors will diminish as the child adjusts to this time in their life. As long as the child isn’t hurting themselves or others, any expression of grief is normal and okay.

When a death happens, children worry about how it will affect their life and who will be there to take care of them. They may worry about another death occurring or about who will take them to school. Providing information about their schedule and who will meet their needs can decrease their anxiety.

Grief comes in waves. It is not unusual for children to be very emotional or ask a lot of questions and then suddenly appear not to be impacted by the death. This is their way of taking in only as much as they can handle at that time. They may return with many emotions or questions along with the need to retell their story over and over.

Support for the Grief Journey

As children grow, their grief will evolve. This experience is a part of who they are and things will never go back to the way they were. They may re-experience their grief as they reach various milestones. It’s important to check-in with them and support healthy ways for them to re-process their grief.

Your local bereavement organization may offer programs and ways to support your child throughout their life. Resources, like a peer, grief-support group, provide opportunities to learn from others and feel less isolated. Many of their friends have not experienced something like this, so groups help to normalize their grief and create a helpful support system.

The most important way for you to support your child is to model healthy grief responses. Children learn about grief from watching the adults in their lives. Reach out to other family, friends, or professionals for care and support. Find activities that acknowledge your grief and allow you to remember the person who died. Be patient and give yourself time.